- India

- International

Delhi’s Urdu Bazar and the decline of a language

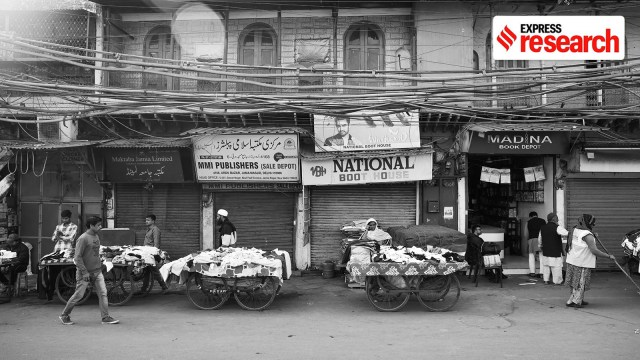

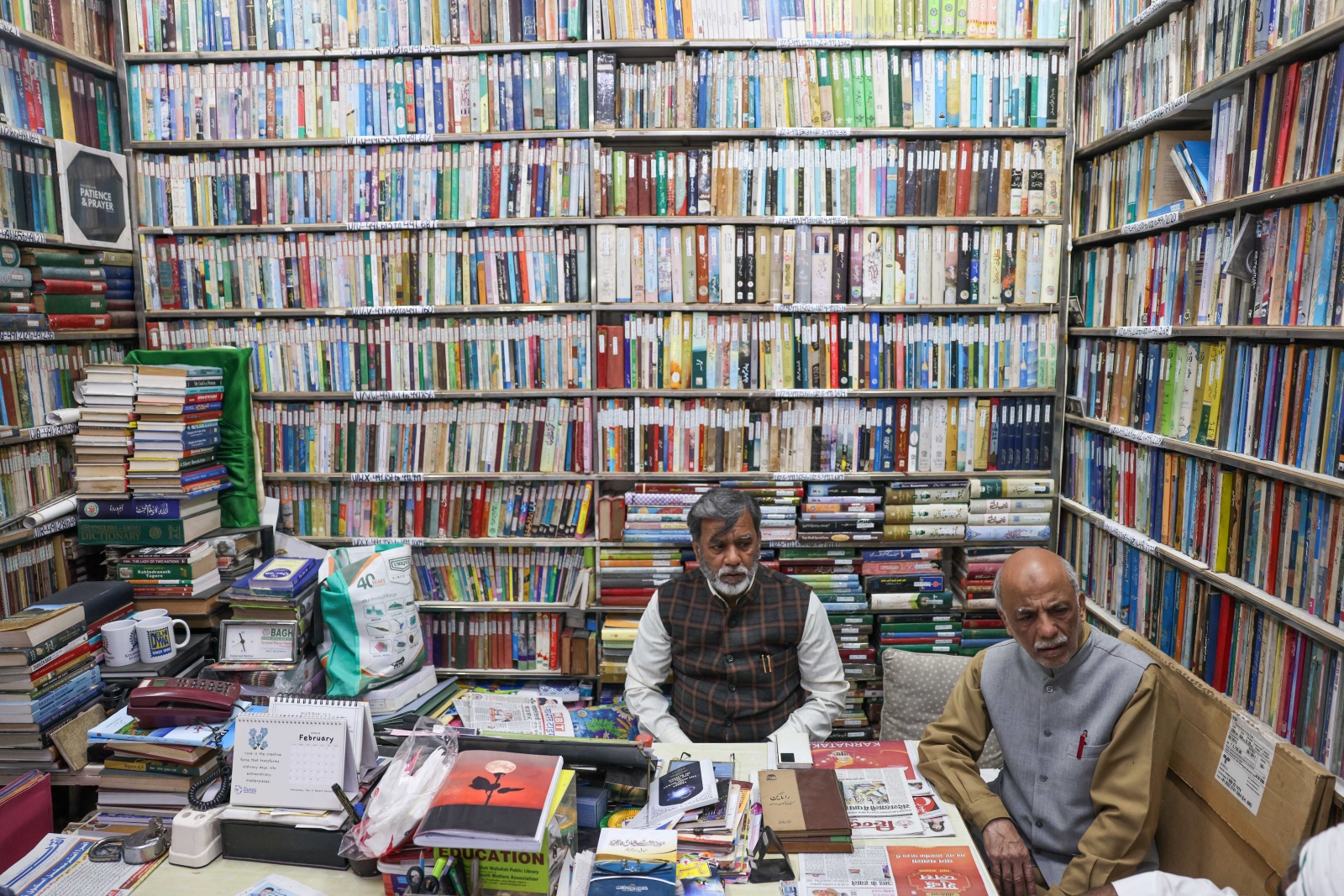

Nestled opposite the Jama Masjid in Old Delhi, the Urdu Bazar was once upon a time a bustling hub for the city's literary community. Even till about 40 years back it was studded with bookstores. Today, barely six are left.

Just about 40 years ago, almost 80 bookstores lined up from Jagath Cinema to the entrance to Matia Mahal Road. Today, barely six bookstores are left. (Chitral Khambati)

Just about 40 years ago, almost 80 bookstores lined up from Jagath Cinema to the entrance to Matia Mahal Road. Today, barely six bookstores are left. (Chitral Khambati)On a quiet Saturday morning, the aroma of freshly brewed tea hangs in the air of Urdu Bazar, a market now relatively empty compared to its former vibrancy. Nestled opposite the grand Jama Masjid, Urdu Bazar was once a bustling hub for Delhi’s literary community. Now, a sense of quiet prevails. Most shops open only after midday, waiting for customers. The booksellers, sip tea and watch tourist buses pass by, waiting for a passionate reader to browse their collections.

Just about 40 years ago, almost 80 bookstores lined up from Jagath Cinema to the entrance to Matia Mahal Road. Today, barely six bookstores are left. The air that was once filled with discussions of Ghalib and Faiz’s poetry is now thick with the aroma of sizzling kebabs. The booksellers admit to the decline in business. Yet, a handful of them continue to adapt to the changing conditions to protect their history and family heirloom.

“If you wanted to pick up a book in Urdu during the 1970s and 80s, you came here. But over the last 15 odd years gradually the demand of Urdu books has petered out and this is the result of the step-motherly treatment that this language is given,” says history enthusiast Sohail Hashmi in an interview with Indianexpress.com

The beginnings of the Urdu Bazar

The name Urdu Bazar came up during Emperor Shahjahan’s reign even though it did not have any connection to the Urdu language or books. The word ‘Urdu’ originates from the Turkish word “Ordu”, which means ‘army’. Since the Mughal army was stationed here, the name Urdu Bazar became popular.

Hashmi, says that in the 17th century, when the Mughal capital shifted from Agra to Delhi, the area between Red Fort and Jama Masjid, where the Urdu Bazar stands now was the open ground for army camps. The area, until 1920 was called the Urdu Mandir or the Lashkari Mandir.

Various bazaars or markets were developed around these camps to sustain the daily needs of the army. In fact, until the 19th century, the word ‘Urdu’ did not signify any language at all.

Hashmi mentions that the Urdu language developed among the working classes such as the army and the peasants. Most of the officers and political elites spoke Turkish or Persian. Even Mirza Ghalib wrote in Hindi. It was only much later in the mid-19th century that the British began to address Hindi or Rekhta as Urdu. That is how Urdu came to be associated with a particular language.

In the early 19th century, the lanes outside the Jama Masjid had small publishing shops, a few bookstores and calligraphers (katibs). However, the entire stretch of land from the Red Fort to the Jama Masjid was demolished after the Revolt of 1857. Historian Swapna Liddle in her book, Shajanabad: Mapping a Mughal City, writes that the only major structures intact in this area after the Revolt of 1857 were some temples, nothing else survived.

The demolition after the Revolt of 1857 was massive, says historian Amar Farooqui. Almost two-thirds of the fort was demolished alongwith the adjoining residential areas, including what was then the Urdu Bazar, he says.

Even as the Urdu Bazar was destroyed in the aftermath of the 1857 Revolt, its name and memory remained in the hearts of the people of Old Delhi. Decades later, a new Urdu Bazar came up, this time in the vicinity of the Jama Masjid where it stands to date.

Revival in the 20th century

Months after the 1857 rebellion, civilians started returning to Delhi and markets began to develop. However, the present-day Urdu Bazar did not begin until the 20th century.

Farooqui says Urdu Bazar started in the 1920s along the street from Jagath cinema to the bylane leading to Matia Mahal. The Bazar had religious books, political tracts, and historical accounts. “If you wanted to buy some recently published work of literary criticism on Ghalib or Momin, you would go to Urdu Bazar,” he says.

Hashmi recounts that throughout his childhood and his university days, if anyone wanted to buy a book in Urdu, Urdu Bazar was the place to go.

Up until the 1960s, Farooqui mentions that the bazaar also had a collection of Persian literature and Arabic books. Primers that helped to learn these languages and teach them were also sold in the bazaar.

At its peak in the 1970s and 1980s, the bylanes were also studded with bookshops. Gradually, Urdu Bazar became the centre of Urdu printing, publishing, and writing.

Urdu Bazar started in the 1920s along the street from Jagath cinema to the bylane leading to Matia Mahal. (Chitral Khambhati)

Urdu Bazar started in the 1920s along the street from Jagath cinema to the bylane leading to Matia Mahal. (Chitral Khambhati)

Farooqui believes that there is a technical reason why Urdu publishing and selling of books were conducted in adjoining markets.

Before computers, printing Urdu, Arabic or Persian required a litho press or a lithograph. A katib would use a special ink to write on yellow paper which would then be transferred onto a zinc plate for printing purposes. Many Urdu publishing houses were located in Daryaganj, a few kilometres away from the Urdu Bazar. Booksellers in Urdu Bazar shared a close relationship with these publishing houses and often sourced their books from there. In a way, the publishing houses became an extension of Urdu Bazar.

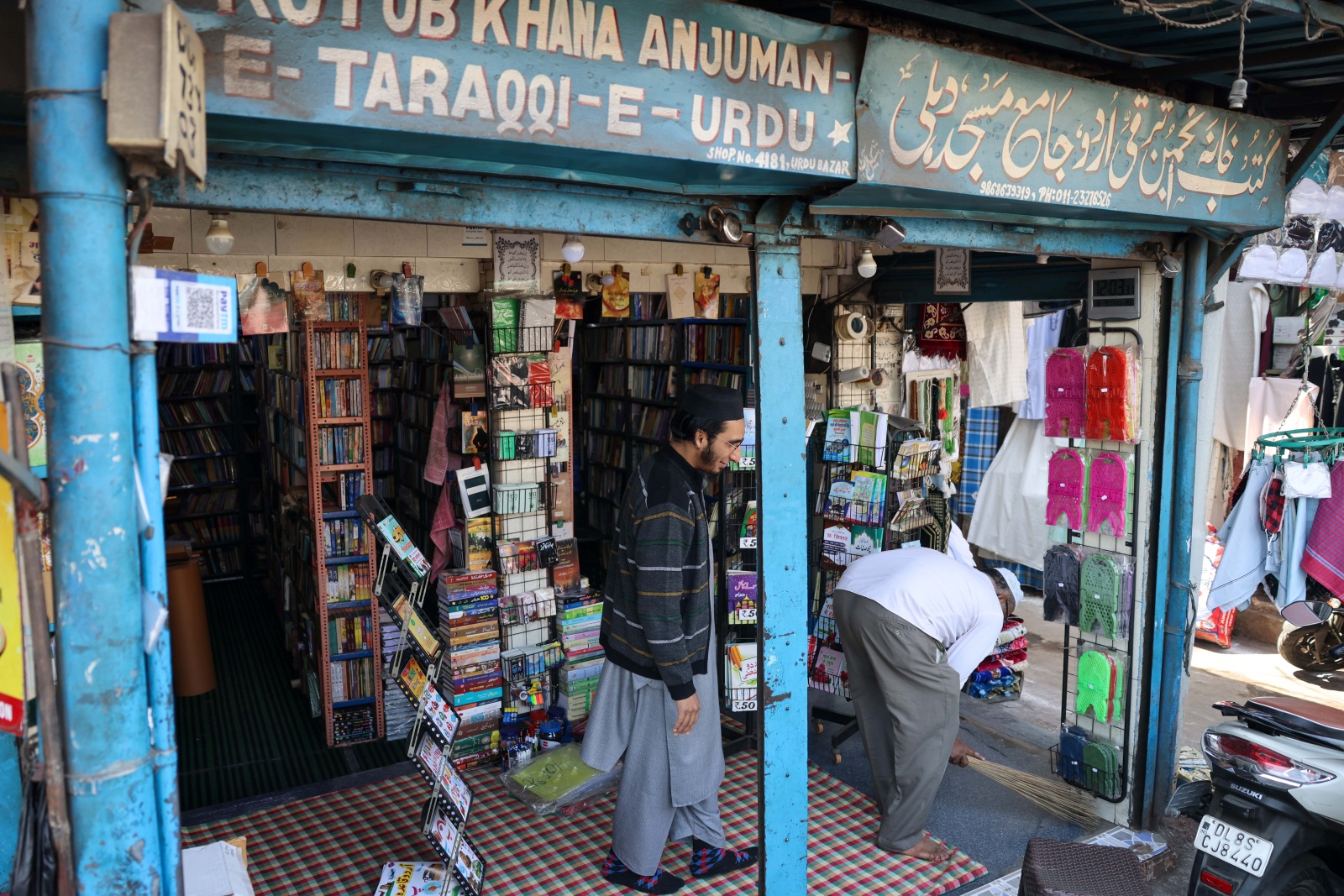

Even within the Urdu Bazar, several shops specialised in particular genres of books. Kutub Khana Rashidia specialised in the Quran and other religious texts. One of the oldest and most celebrated bookstores, Kutub Khana Anjuman-e-Taraqqui-e-Urdu, also sold stationery along with a wide collection of Urdu literary and criticism.

Until the late 1970s and early 80s, Farooqui recalls, Urdu Bazar also had a fish market. People would call the area ‘macchi wala’. Jagath Cinema, Urdu Bazar and the wholesale fish market thrived together, breaking barriers between the intellectual and working classes.

The area around Urdu Bazar underwent its second demolition during the Emergency in 1975. Many parks and centres of social gatherings were razed. In the 1980s the fish market also moved out to Ghazipur, near the Delhi-Uttar Pradesh border, thereby permanently changing the landscape of the area.

By the mid-1980s, Farooqui says, the decline of the Urdu book trade and publishing had already set in. In retrospect, however, he associates the decline of the Bazar with the decrease of bookstores across the city. “Connaught Place is a prime example,” he says. Once a hub for prominent bookstores, it now has very few.

Declining 21st century

Reminiscing about the 1970s and 1980s, 58-year-old Sikander Changezi, a resident of Old Delhi, says it was common for famous poets to hold mehfils and recite poems at Urdu Bazar. They would often engage in intense debates and discussions. But in the mid-1980s, when adjoining restaurants and other food stalls started becoming popular, visitors to the bookstores started declining.

In the last 10 years, nearly 15 Urdu bookshops have shut down. Today, there are hardly six bookstores in the lane from Jagath Cinema to Matia Mahal.

Mohammad Rehman, the owner of Kutub Khana Rashidia, receives approximately 20 customers a day. However, most customers are in search of religious texts, such as translations of the Quran. “Very few people come to buy literature, political treatises or history books. Sales of these books have dipped by half in the past 10 years”, he says, adding that the youth is no longer attracted to reading or literature. “It is not just about the Urdu language but for other languages as well, people are simply not reading nowadays.”.

He says Urdu Bazar has now become “Khana Bazar (food market)”.

Mohammad Rizwan, who owns a small makeshift bookstore with a foldable bench, concurs. “After my father passed away and the property was divided, I was left with this much. I am the only one in my family who continues to sell Urdu books,” he says.

Rehman attributes the decline to the advent of the internet. He claims that people are distracted by meaningless videos and reels. “They refuse to acknowledge that books are the foundation of culture and civilisation,” he says.

In the last 10 years, the sales of Urdu books have decreased by half. However, the demand for religious books such as the Quran and Hadith has not changed drastically, he notes.

Farooqui believes that by the mid-1980s and early 1990s, the technological landscape changed drastically enough to impact the Urdu Bazar. Several katibs, who sat in front of bookshops, lost their jobs because lithographs were not used anymore for printing. Along with the Urdu Bazar, the surrounding economy of printing and publishing also began to decline.

The future of Urdu Bazar and language

Despite bookshops shutting down rapidly, many are optimistic about the revival of the Urdu Bazar and the Urdu language itself. Changezi along with Mohammad Naeem, another resident of Old Delhi, started the Hazrat Shah Waliullah Public Library which hosts a collection of rare manuscripts and over 20,000 books. Located just a few lanes away from the Urdu Bazar, the library, established in 1994 under the Delhi Youth Welfare Association, attempts to recreate some charm of the market.

Sikander Changezi along with Mohammad Naeem started the Hazrat Shah Waliullah Public Library which hosts a collection of rare manuscripts and over 20,000 books. (Chitral Khambhati)

Sikander Changezi along with Mohammad Naeem started the Hazrat Shah Waliullah Public Library which hosts a collection of rare manuscripts and over 20,000 books. (Chitral Khambhati)

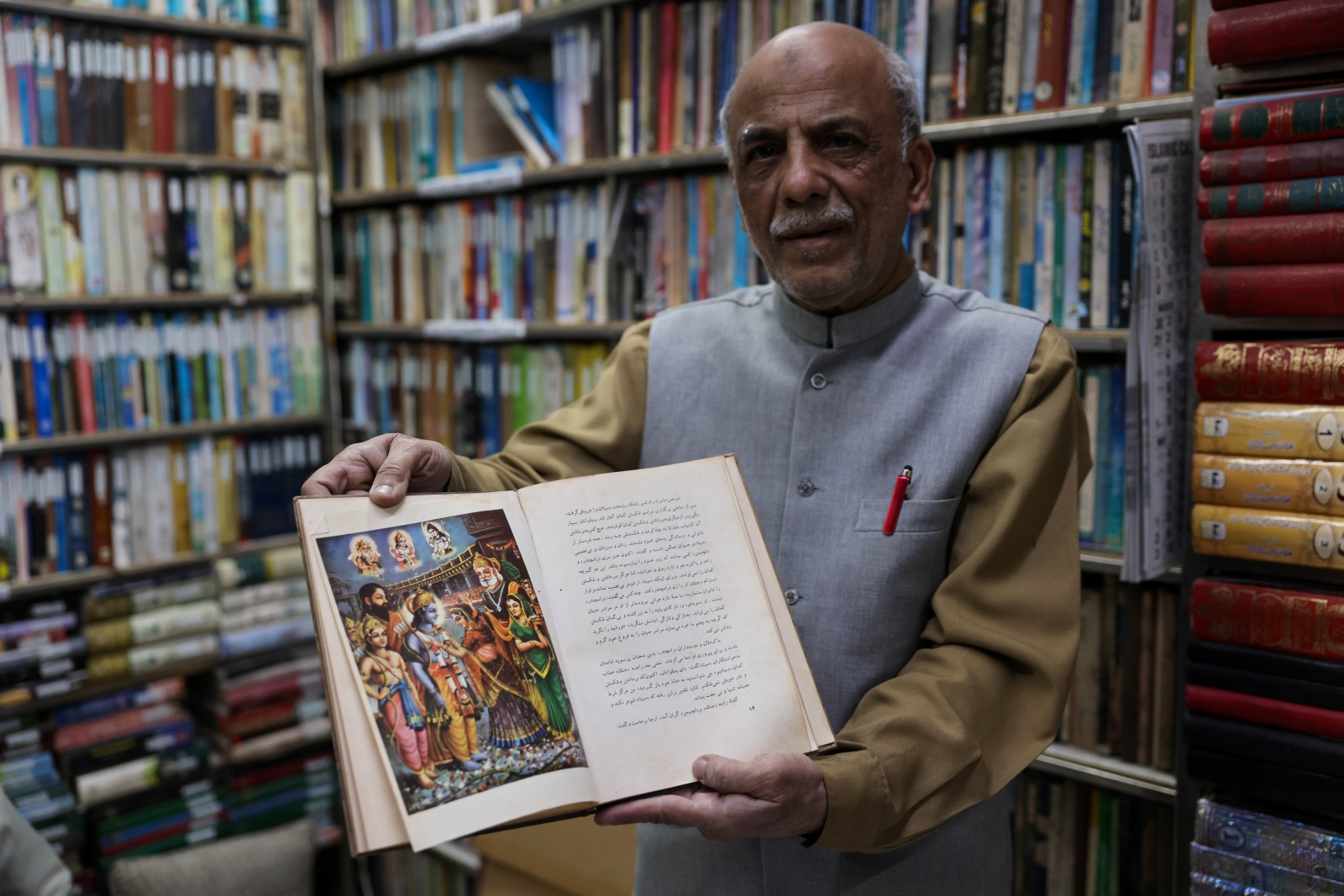

Among the diverse collections of the library are over 700-year-old Arabic manuscripts on Islamic Law and a 100-year-old Quran with every page written in a different style. The library also holds Persian translations of the Ramayana, the Bhagwad Gita, and Diwan-i-Zafar, the poetry collection of the Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar.

Describing the mission of the library, Changezi says “To impart wisdom you need to have books, for books you need a library”.

“Often online, readers can’t find the depth of rare information that is available in a library,” says Naeem.

Sikander Changhezi holding the Persian translation of the Ramayana (Chitral Khambhati)

Sikander Changhezi holding the Persian translation of the Ramayana (Chitral Khambhati)

Along with Arabic and Persian, Hazrat Shah Waliullah library also has many Urdu books, which are not only limited to literature and manuscripts but also school textbooks. Changezi and Naem’s library facilitates the education of many children in Old Delhi as it also functions as a coaching centre in the afternoon.

When the library began in 1994, Naeem and Changezi noticed high dropout rates from schools in Old Delhi. “Young children hardly studied beyond the eighth grade here. Today where the library stands, youngsters would play cards. That was the atmosphere we wanted to change,” says Naeem.

Apr 04: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05